This Informed Investor page contains a few articles that Joseph Shaefer has published discussing various investing disciplines and approaches.

It also contains book reviews he has written on what he considers the very best investment books. There are no stock, ETF, mutual fund or specific strategy recommendations here.

These are articles that offer the basis for intelligent thinking about the markets, not specific advice or recommendations for your further due diligence.

(If you want to discuss portfolio management or our private investment letter site at Seeking Alpha, you are welcome to contact us directly or explore our site further.)

What is Our Current Market Forecast?

“It will fluctuate.”

My answer is not intended to be glib or flippant. It is, in fact, what the steely-eyed gentlemen in the photograph, J.P Morgan, replied when asked the dull-witted question as to what the stock market would do that week.

He gave the only honest answer a man can give. J.P. Morgan didn’t know what the market would do the next day. Neither do I. Neither does anyone else. Yet there is an entire sub-industry of people buying expensive TV ads and bombarding you via e-mail and your mailbox, So-and- Sos Startling Prediction for Tomorrows Market! Buy Our Service Today!!!

Seriously now — if they really knew what the market was going to do or what stock would return 1000% or more, why wouldn’t they just buy it and retire rich rather than trying to sell you their predictions / guesses? Yet every day otherwise-intelligent people line up and scramble to get to the front of the line to buy this hooey!

Forget the shrill and the charlatan. Instead, build a portfolio, balance your portfolio across asset classes, stock it with quality funds and firms from around the world, and be willing to sell when the time is right. Concern yourself with asset allocation and cyclical — not secular — timing before you even move on to stock selection.

So, rather than give a Market Forecast for tomorrow, we offer instead our our services in creating for you a Market Philosophy for a Lifetime. — J L Shaefer

To achieve Certain Wealth in Uncertain Times ….

Anyone can make money when the market is going up. The key is — don’t give it back when the market declines. To do this, we have concluded it is essential to identify contracyclical sectors, look beyond US borders, and delve into long/short mutual funds and ETFs, convertible securities, high-yielding stores of value, rising rate funds, and so on, in order to try to increase our net worth in good times and bad — in certain times and uncertain times.

A client recently asked how I could write favorably about a company, then be willing to sell it four months or a year or ten years later. The answer is simple: stock selection is the least important, but potentially the most dangerous, investing decision. Let me explain…

There are certain companies that are well-managed, well-capitalized, treat their employees right, and are growing their sales and their earnings while increasing their market share. I like those kind of companies!

If the market conditions are favorable, and the companies are in a sector whose stocks I believe will do well over the coming six months to infinity, that company’s stock might even be appealing. Very often I really like a company, but would not touch their stock because it is overpriced. But if the stock has experienced a decline in share price because of what I consider a temporary and/or overblown phenomenon (like missing some analyst’s earnings guess by a penny) it may represent great value. That’s when I want to buy it!

If I like the company and I like the stock, why am I then willing to sell just a few months or years later? Well, if the same market factors are in place (the bull is still intact) and the sector is still attractive, I will hold and hold and hold. But, remember, stock selection is only one part of the investing decision. If the market looks infirm or terminal, I want out.

Even the greatest company whose stock is cheap won’t completely resist a secular decline. And if the sector turns cool then I will use trailing stops. These stops may mean that I abandon the entire sector and wait for prices to plummet before re-entering.

The bottom line? I am faithful to a methodology and a discipline. I may get excited with a great company’s vision and execution. But I never, ever, fall in love with a piece of paper (the stock) that is just minuscule ownership in a particular company. Great companies are always being born or reborn.

Sometimes their stock prices are attractive. Sometimes they are not. But the market and the sector have more to do with the price appreciation you and I will enjoy than even the best-selected stock. Most people waste an investing lifetime saying, “just tell me which stocks will go up.” This leads them to fall for the charlatans out there who give the marks what they ask for.

Successful investing is more complex on the buy side and far more complex on the sell side. If it were easy, anyone could do it. Most fail. For me, with my particular discipline, if any of the key factors of market direction, sector, or share value change, it can trigger a decision.

Please don’t seek shortcuts when viewing the Investor’s Edge portfolios, either! I was told by a subscriber recently that he didn’t need an investment adviser. His sure-fire way to do well was just to buy everything in our Growth & Value Portfolio with a # next to it, meaning that I or someone else at Stanford Wealth Management owns the stock. I was aghast.

Don’t buy just those I hold! Like you, I have money to invest some months and I am out of Schlitz other months. If I just bought 2,000 XYZ for $50,000 it doesn’t matter how highly I regard some stock I uncover in the next couple weeks, I am out of money until I sell something or until I earn more money. I cannot buy everything I analyze and conclude is an appropriate investment for the market we are then in. Since it is quite certain that I will never be burdened by the demands of inherited wealth, what comes in to my bank account comes solely from my work and the capital gains I enjoy from my investment portfolio.

As I’ve matured (OK, gotten older) more and more of the increase in my net worth comes from intelligent investing rather than business income. My lifestyle and future improve primarily by what I buy and sell. My suggestions to you come from the research I do to keep the wolf from the door. I can’t afford to chase some hot stock — this is my nest egg. That is why I invest in a methodical, coherent, and disciplined manner.

That is also, as I answered my client’s question, why I am able to select, but also to abandon, the pieces of paper that represent my ownership in great companies: if the company hits a serious speed bump, or the market looks weak, or the sector looks tired, or the stock becomes overpriced, it is time to move along.

One final thought on stock selection and retention (the “keep it or not” decision): diversify across industry, sector, and region. If you are going to use the kind of disciplined approach I use, you must buy more than just one of the stocks I recommend. Just as you should not say, “just tell me what stocks will go up” don’t even think”this is the one (or two or three)that have to go up.”

What I write about a particular industry may strike a responsive chord with you, but that doesn’t mean you should buy only my recommended stocks in only that industry. Invest in a cross-section of sectors and companies and always do your own due diligence! If you do, I believe you will slowly and surely gain “Certain Wealth in Uncertain Times.”

— J L Shaefer

Timeless Investment Classics (Part I):

The Best Book Ever Written About Market Psychology

Not to disparage any investment book hot off the presses in 2017 or written in the last 40 years (including my own!) but to be considered a “classic” the book must have stood the test of time. I figure 50 to 180 years should provide a pretty good crucible. I believe these books can teach us more about human nature, investing, and wealth and risk management than anything written before or since.

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

Charles Mackay 1841

You may be excused for wondering what a book published 169 years ago could possibly teach you about today’s markets. Not only had CDS’s and sub-prime mortgages not been invented, but in most parts of the world stock markets themselves had not yet been invented! But never forget – financial markets are subject to, sometimes dependent upon, and often ruled by, the whims of human nature. Human nature is as timeless as the stories from the Bible, the Torah, the Koran, the I Ching and every other compendium handed down orally until finally set down on leather, papyrus, or paper. And no one has described the follies of humans more cogently than Charles Mackay in 1841.

I believe Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds is the best book ever written about market psychology. It includes case histories–long before case histories became a standard teaching tool–of three infamous financial manias.

- Tulip mania was a financial bubble in the 1620s and 1630s in Holland when contract prices for tulip bulbs reached amazingly high levels before collapsing. At the height of tulip mania in February 1637, a single tulip contract sold for more than 10 times the annual income of a skilled craftsman. Then it all fell apart.

- John Law’s early 1700s Mississippi Scheme, foisted by a Scottish economist mostly upon his French neighbors, in which the “untold wealth” of “Louisiana” (what the French called America and the Caribbean) was to pay off in no time at all. The excitement was so great that he issued considerably more paper shares than there was money in the Banque Generale Privee, at that time effectively the central bank of France — which he was head of — and which was effectively the guarantor of all that paper.

- The South Sea Company was established on the British side of The Channel about the same time. It was granted a monopoly to trade in Spain’s Central and South American colonies as part of a treaty after the War of Spanish Succession. In return, the company assumed the entire national debt England had incurred during that war. (Europeans used the term “South Seas” to refer to the waters surrounding South America.)Established by the Lord Treasurer, Robert Harley, what Harley didn’t mention, and apparently no one bothered to ask, was that, as part of the treaty with Spain, the South Sea Company was allowed to send only one trading ship per year to Spain’s American colonies! Still, people in that heavily class-conscious society, from the lowest to the highest, threw money at the venture as the company employed “the most extravagant rumours” to pump the share price from 100 Pounds to 1,000 Pounds in less than a year. All lost except those within the government and the nobles who had never really paid for their shares but were invited to accept shares in exchange for the use of their august names.

But Mackay doesn’t stop with a case study of each of these early manias.The book is part history, part thriller with enough colorful and crazy characters and anecdotes to read more like a novel. And he includes chapters on other “popular delusions” beyond the financial arena, including chapters on alchemy,The Crusades, the witch mania and the European witch trials of the 1400s-1600s, prophecies, fortune-telling, catch phrases & slang, relics, duels & ordeals, haunted houses, & popular admiration of thieves.

If that isn’t enough to whet your interest, let me suggest that you cannot understand the dot-com phenomenon or the real estate bust nearly as readily without studying how it’s all happened before. Remember, nearly $1 and ½ trillion was invested in Internet stocks by some of the savviest investors in the world. When it was all said and done, that trillion and a half had been reduced to less than $100 billion. We all lived through it. But some of us sidestepped it. I attribute that partly to my recollections of readings from this book.

By understanding the patterns of greed and hope, and the ready willingness of charlatans to step forward to give us what we want, we might avoid the pitfalls that inevitably follow. If you understand that, when someone utters the words, “This time it’s different” you are in the end-stages of a popular mania and can extricate yourself, you just might save your entire fortune.I’m guessing that the rank-and-file Enron employees, who sunk their entire life savings into Enron stock, wish they would have done so.

This book is more than a book on intelligent investing – it is really a classic in critical thinking. Anyone can learn how to read a chart or throw bones into a circle, but this book will teach you about human psychology. That is how you beat the market, since it is always a marketplace of humans motivated by fear, greed, hope, arrogance and all the other human emotions, good and ill…

What I take for action from this re-reading of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds is that the “prevailing wisdom” is less about wisdom than it is the prevailing combination of hopes, fears, greed, arrogance, wishes and prayers that enough people fervently want to believe in. And that man is a social animal influenced by others in his social, business, personal, reading or Internet-surfing circle, a circle he defines based upon his own biases, upbringing, prejudices, experience, and the comments and approbation or criticism from those around him.

So, in 1929, many years after Mackay wrote this little gem, that combination of hopes, fears, wishes and prayers that enough people fervently want to believe in led them to believe they were on a permanently high plateau from which companies could never fall. In 2000, the same geist / sentiment prevailed in regards to dot-com companies. It was The New Economy, A New Paradigm, The New Reality. No it wasn’t. Any more than home prices, circa 2006, could never fall in San Francisco, Las Vegas, Miami or wherever the proponent of exponential growth wanted so fervently to believe in.

— J L Shaefer

The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind

Gustave Le Bon, 1896

As Gustave Le Bon wrote in the introduction to this slim little gem six generations ago, “The substitution of the unconscious action of crowds for the conscious activity of individuals is one of the principal characteristics of the present age.” No truer words were ever spoken about the psychology of how people tend to invest in this “present age”!

Why is it that otherwise rational people take on a herd mentality when investing and seek the comfort of knowing that hundreds of thousands of like-minded individuals think as a group and share their biases and perspective? Is it because the lonely path of iconoclastic thinking and contrary investing may yield better results but is also, well, lonelier? To be wrong when all others are right, even if that latter path yields them little or no return, is to subject oneself to the derision of the social unit. And to be right when all others are wrong, even if that former path is wildly profitable, is to subject oneself to the envy and resentment of the social unit. It takes a strong individual to be an individual.

I hasten to point out that The Crowd was not a book written about the stock market. Au contraire! It was written to try to understand group psychology, whether the group was a criminal organization, an electorate, a jury or a parliament. But understanding the group dynamics of each of those is a good practice ground for understanding the emotions and actions of one camp or another when debating a stock, an industry or a sector. And The Crowd offers, via these other avenues, unique insights into what makes people do the things they do from within the warm incubator of like-minded individuals.

In that light, how different is the following observation of the French Revolutionaries (from page 187 of my 1952 Ernest Benn Ltd edition) from what many of us see in certain of our national-level politicians today…

“The most perfect example of the ingenuous simplification of opinions peculiar to assemblies is offered by the Jacobins of the French Revolution. Dogmatic and logical to a man, and their brains full of vague generalities, they busied themselves with the application of fixed-principles without concerning themselves with events. It has been said of them, with reason, that they went through the Revolution without witnessing it.”

At its lowest level of over-simplification, Le Bon’s thesis in The Crowd is that the behavior of crowds is based on sentiment and emotion rather than intellect and research. That may seem rather obvious today since other social scientists have been agreeing with and building upon his work for over a century. But how many of us invest accordingly? Do we seek to understand the hope, fear, greed, mistakes and misinterpretations of the crowd or do we seek to find “facts” for why the market rises or falls on a given day, week, month or year?

Most of us want to know “why” the market declined today. We are satisfied when we hear the evening news: Oh, it was because Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) declared lower sales of its iPhone. Or because Goldman was sued by the SEC. Or because Greece is not going to get a full bailout from Germany. Ah, we say – now it makes sense. Of course it went down.

Le Bon would no doubt say, “Faaahhh on your reasons.” It declined because there were more sellers than buyers so the price began moving downward to attract more buyers. It declined because more people became nervous, or got a wild hair from something they overheard at the giant media water-cooler, or received a message on their dentures from alien life forms. It is sentiment that moves crowds, not reason. And being a member of a crowd causes one to behave differently from the way one would behave as an individual.

Le Bon saw crowds as a psychological phenomenon rather than a physical one. Individuals can form a crowd having never met or come together simply by having a common cause. This type of influence can easily be found in groups such as members of a particular occupation or calling, religious sects or even entire religions, sports teams and their fans, and so on. Then there are the crowds of advocates for the bullish camp and the bearish camp in any market. Market agnosticism is a very difficult path to tread, yet it seems to offer the best hope of long-term success.

That is because of two concepts offered by Le Bon. First, a crowd effectively has a mind of its own and, second, individual behavior is altered by membership in the crowd – often to the point of subjugating misgivings or original thinking to the will of the crowd. That’s why I have suggested in a number of previous articles that you decide who to listen to – including here on SA – by how successfully the writers have made you money, not by how much you agree with their dogma or rhetoric on the government, the economy or the market.

I heartily recommend this book to you, just as I did the first in this series, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds by Charles Mackay. Yes, both are written with what we today might consider a certain quaintness of style more popular in the 1800s than in today’s frenetic, multi-tasking, cut-to-the-chase tweeting and twittering. So – investing-wise: how’s that working out for you?

— J L Shaefer

Reminiscences of a Stock Operator

Edwin LeFevre, 1923

“It never was my thinking that made the big money for me. It always was my sitting. Got that? My sitting tight! …Men who can both be right and sit tight are uncommon.” — Edwin LeFevre

“I never attempt to make money on the stock market. I buy on the assumption that they could close the market the next day and not reopen it for five years.”– Warren Buffett, who obviously read his Edwin LeFevre

Reminiscences of a Stock Operator is a barely-disguised biography of Jesse Livermore, a Wall Street legend who made and lost a number of fortunes.Mr. Lefevre has taken a very close look at what worked and what didn’t for Mr. Livermore and come away with some remarkably insightful observations about investing, speculating, trading and the nature of the market and its players.

Reminiscences of a Stock Operator is a barely-disguised biography of Jesse Livermore, a Wall Street legend who made and lost a number of fortunes.Mr. Lefevre has taken a very close look at what worked and what didn’t for Mr. Livermore and come away with some remarkably insightful observations about investing, speculating, trading and the nature of the market and its players.

Remember when reading this book, it is written as a novel, not a biography or an autobiography. I say this because it is so thinly-veiled that scores of quotes are today attributed to Jesse Livermore, when in fact they were penned by journalist Edwin Lefevre and spoken by his protagonist “Larry Livingston.” That’s not to say that Jesse Livermore may not have said the same thing or something nearly like it, but it was “Livingston” to whom it can be traced. I use the character and the flesh-and-blood character interchangeably; throughout the book, you may well feel as if this was Livermore’s “as told to” authorized biography, and it may well have been.

Among my favorite thoughts in the book that has guided my investing for 40 years is, “I learned early that there is nothing new in Wall street. …Whatever happens in the stock market today has happened before and will happen again.” That does seem particularly timely of late.

The first part of the book provides some background for the young trader, describing “Livingston’s” early career as a young boy working in a “bucket shop,” so called because it was there that speculators placed stock “bets” with operators who were often swindlers; they never actually executed buy or sell orders but, instead, threw them into a bucket. They knew that the vast majority of bets would be wiped out by minor fluctuations, allowing them to pocket the funds based on their “margin rules” and such. Sort of like bank trading desks today, only with nicer personalities.

Young Livingston learned his craft here from years of daily observation, and he then swindled the swindlers by using their own tricks against them. He became a dedicated tape reader who developed an acumen for anticipating price fluctuations. He amassed his first fortune from these trading activities, so successfully that the bucket shop operators banned him from “playing” anymore, so he moved on to the Big Casino of Wall Street trading firms.

If you are a buy-and-hold investor, Reminiscences of a Stock Operator may not convince you to become a stock trader but it will still help you become a better long-term investor. How? Because the speculative ploys described in the book will allow you to see who is arrayed against you today and help you understand that there is absolutely no difference between what the Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GD) traders do and what the speculators of 1923 did, except maybe the price of their suits.

Livingston / Livermore’s approach was the very antithesis of buy-and-hold; his was the intellectual groundspring from which all the relative momentum traders of today have come. Just determine the path of least resistance in the market and never fight the tape. He did no fundamental analysis or attempt to determine a likely top or bottom. Instead, he waited for a trend to be confirmed and then jumped in with large bets. If there was no defined trend he waited patiently on the sidelines.

I am someone whose natural temperament, along with the time I am willing to spend watching every tick of the market, pushes me to calm, reflective fundamental analysis and a long-term point of view, so you might be surprised to find that one of my best “fundamentalist” disciplines comes from Reminiscences of a Stock Operator. Any fundamentalist’s natural propensity is to buy low and sell, if at all, much higher. That sometimes makes us believe that, just because we bought something at 15 and added a little at 17, that at 25 it must be too dear. I learned from this book to stop selling my own analysis short.

The biggest coups I have made in my career have come from identifying an undervalued situation and a probable catalyst early (very un-Livermore like) but then adding to it regularly – averaging up – as long as my analysis still held (very, very Jesse Livermore.) It’s a pleasure to watch as others catch on to something I discerned a month or a year earlier, but more pleasurable yet to continue to profit by it.

From this book I learned to add to my best ideas as long as their trend is still moving exactly as I imagined it would, which I recommend to you whether you are a trader or investor. And do cut your losses. It’s OK to be wrong; it’s not OK to be broke. If the rest of the investing world disagrees strenuously with you choice, don’t average down; keep most of your portfolio intact and be able to come back with a different idea.

In this, Livingston and Livermore and I are well in sync.You have to be patient, he wrote: if things are going your way, stay the course and don’t succumb to the occasional quick profit. He also noted that, for him, value plays no part in the decision, since prices move with the greed or fear of the crowd. That’s why he believed, and proved in his own accounts, that a stock is never too high to buy or too low to sell .

Although the book purports to accurately describe the highs and lows of Livingston / Livermore’s roller-coaster life, the real take-aways come from the trading decrees that are now trading maxims around the world. For instance, the concept of a public that regularly vacillates between greed and fear is on page 130 of my edition. The maxim “Never average down” on page 154. Among others that came directly from this book are “The trend is your friend,” “No stock is too high to buy or too low to sell,” “Let your winners run and cut your losses quickly,” and “if you don’t like the odds, don’t place a bet.”

Among some others I think you may find of value, even in, especially in, our own troubled times are:

“What beat me was not having brains enough to stick to my own game – that is, to play the market only when I was satisfied that precedents favoured my play… No man can have adequate reasons for buying or selling stocks daily – or sufficient knowledge to make his play an intelligent play”

“… the automatic closing out of your trade when the margin reached the exhaustion point was the best kind of stop-loss order.” [JLS: Or, Never meet a margin call!]

“I knew of course, there must be a limit to the advances and an end to the crazy buying of A.O.T.-Any Old Thing-and I got bearish.”

“ My relations with my brokers were friendly enough. Their accounts and records did not always agree with mine, and the differences uniformly happened to be against me. Curious coincidence–not! But I fought for my own and usually won in the end. They always had the hope of getting from me what I had taken from them. They regarded my winnings as temporary loans, I think.”

“ They say you never go broke taking profits. No, you don’t. But neither do you grow rich taking a four-point profit in a bull market.”

“… the big money was not in the individual fluctuations but in the main movements–that is, not in reading the tape but in sizing up the entire market and its trend.”

“Disregarding the big swing and trying to jump in and out was fatal to me. Nobody can catch all the fluctuations. In a bull market the game is to buy and hold until you believe the bull market is near its end.”

“When I am long of stocks it is because my reading of conditions has made me bullish. But you find many people, reputed to be intelligent, who are bullish because they have stocks. I do not allow my possessions – or my prepossessions either – to do any thinking for me. That is why I repeat that I never argue with the tape.”

“… I came to learn that even when one is properly bearish at the very beginning of a bear market it is not well to begin selling in bulk until there is no danger of the engine back-firing.”

“Sell down to the sleeping point.”

“He will risk half his fortune in the stock market with less reflection that he devotes to the selection of a medium-priced automobile.”

“He should accumulate his line on the way up. Let him buy one-fifth of his full line. If that does not show him a profit he must not increase his holdings because he has obviously begun wrong; he is wrong temporarily and there is no profit in being wrong at any time.”

“When a stock is going up no elaborate explanation is needed as to why it is going up. It takes continuous buying to make a stock keep going up. As long as it does so, with only small and natural reactions from time to time, it is a pretty safe proposition to trail with it.”

And the one I hew to every single day, “I trade on my own information and follow my own methods.”

— J L Shaefer

Security Analysis

Benjamin Graham & David Dodd, 1934

Published in 1934, Security Analysis was written after 4 straight years of horrendous declines followed by 1933’s 66% rebound.During the time the book was being written, it had been a sideways-ratcheting market with severe thrills and spills.Investors abandoned the stock market in droves and swore never to be burned again.Consumer confidence was at an all-time low, trade declined markedly, retail sales plunged, and unemployment was higher than it had ever been.

Sound familiar? Might there be a corollary to today’s marketplace? I believe there is. I have been hedging client positions and advising SA readers to do the same for months now. Preservation of capital is our #1 consideration at my firm today but, as Chief Investment Officer, I also recognize that 1934 marked the beginning of a more rational market (it consolidated the previous year’s gains by rising 4.1%) and may well be analogous to 2010 and 2011. If so, I want to be prepared to buy a double-dipped, wrung-out, friendless stock market when our well-preserved dollars will go the furthest. Intelligent security analysis may once again separate the successful from the also-rans in the coming months and Security Analysis is there to help.

There are now 6 editions of this work in print. I chose to review the very 1st edition because the theme that runs through all my “Timeless Classic” reviews is that you can be a successful investor without reading a word written in the last 40 years. The criticisms leveled against the 1st edition of Security Analysis is that it was written before the establishment of the SEC so it spends time discussing ways you can and should protect yourself, it was written before listed options and credit derivatives and the Internet and all sorts of other “enhancements” to making money in the market.To this I say the same thing (then-Brigadier) General Tony McAuliffe said to the German commander demanding his surrender at Bastogne: “Nuts.”

This is the classic edition that two professors at Columbia Business School penned together, and in doing so laid the groundwork for everything those of us who think of ourselves as value investors do today. I must warn you up front: this book is very dry in many places and very arcane in reaching deep into balance sheets and income statements in others. It is not an easy read unless you either (a) have some finance and accounting background or (b) are willing to learn. If the latter, you may make forays to the Internet to understand some of the concepts presented. I can only say I believe you will be well-rewarded, both intellectually and financially, if you are willing to do so.

This is the classic edition that two professors at Columbia Business School penned together, and in doing so laid the groundwork for everything those of us who think of ourselves as value investors do today. I must warn you up front: this book is very dry in many places and very arcane in reaching deep into balance sheets and income statements in others. It is not an easy read unless you either (a) have some finance and accounting background or (b) are willing to learn. If the latter, you may make forays to the Internet to understand some of the concepts presented. I can only say I believe you will be well-rewarded, both intellectually and financially, if you are willing to do so.

Graham and Dodd took Wall Street to task (76 years ago!) for its too-short-term focus on quarterly earnings. Sound familiar? Day traders may want to scalp a dime or a quarter on such nonsense but those of us who are value investors have at least a 10-year investing horizon, not one of 12 weeks! In fact, rather than concentrate on “earnings” at all (which they noted could be handily manipulated in any number of ways) they focused on what the business of a particular company would be worth if it were sold at no premium to a willing buyer and what its value would be as a going concern. Graham and Dodd provide a number of convincing examples of the market’s irrationality as some securities were ridiculously over-sought and over-valued by the investing public and others were under-valued as being too boring or simply out of fashion. This is where they saw opportunity for the smart investor willing to view a company as a business, not a momentum play based on “reported” earnings.

Security Analysis is all about helping a disciplined investor determine a fair value for a company from reviewing its various and sundry financial statements, buy these when they are unpopular and underpriced relative to their intrinsic value (a term I believe he coined), and earn a fair return by doing this repeatedly without (and this is terribly important to some of us!) placing your money in a company that is in real danger of a permanent loss because of some shenanigans hidden deep in the footnotes they hope no one reads. (In future editions that Graham wrote himself, he made allowance for the better information available to all that led to the efficient market hypothesis. He still felt strongly, as do I in this age of sector and market ETFs, that some sectors will find themselves out of favor even with the entire sector’s intrinsic value above its market price. In such situations lie opportunity.)

This is a big book, but not because of verbosity or obfuscation on the part of the authors. The language is actually quite modern, the writing quite clear. The book is long simply because it tackles so much, albeit as concisely as possible given the breadth of content. The authors are methodical, rather than scattered, in constructing a gestalt, a macro view, of the analysis and decision-making process they advocate. They begin with a philosophy for investment (as opposed to trading or speculation), follow that with a systematic analysis of different securities, then provide a detailed (too detailed for some!) discussion of financial statements, and conclude with a description of the difference between the intrinsic value of a business and its ever-fluctuating stock price.

Security Analysis contains numerous case studies that are as relevant today as when Graham and Dodd wrote about them. The justifications for the ridiculous prices of dot-com and housing-related stocks in more recent times, for example, are little changed from the IPOs and such that the authors document from the 1930s. And the authors drive home the point that it is simply a waste of time to try to divine to the penny future earnings, and then conclude that if earnings surprise on the upside the stock must rise. They consider that a fool’s errand. This book concentrates instead on actual value. It is about what a company holds on its balance sheet, not what is in the imagination of some paid-to-tout Wall Street analyst. Following that sort of advice ranks as mere speculation for Graham and Dodd, who believe that if you haven’t analyzed an investment’s worth, no matter the source of your information, you are merely speculating. An analysis of the company or sector by you or by someone you trust to do their homework is essential before investing in that company or sector.

But don’t just take my word for it (though I’ll place our ten-year track record against anyone’s!) Warren Buffett was once a student in Ben Graham’s Columbia investment seminar. Buffett is supposedly the only student to earn an A+ in the class, be asked to contribute to a revision to Graham’s other major work, The Intelligent Investor, and make a dollar or two by systematically and judiciously implementing the tenets of Graham and Dodd’s book. Slog through it. You won’t regret it.

— J L Shaefer

The Battle for Investment Survival

The Battle for Investment Survival

Gerald M. Loeb (1935)

My two previous reviews laid the foundation for investing wisdom by surveying the psychology of crowds in financial matters as well as in many other facets of daily living. With The Battle for Investment Survival, we move to our first review of a book specifically published to deal with investing in the securities markets in the United States.

The first two books were well-written and well-organized; The Battle for Investment Survival is not. That’s not to say it isn’t worth reading; it is!! But it’s sort of like visiting a farm where the wheat has been cut but not yet threshed or winnowed: you have to slog through a lot of stalks and chaff to find something you can digest. Once you do that, however, you’ll find it was well worth the work.

The reason why I think this is an important book that deserves to be among the ten investment classics I’ve selected is that the time in which Loeb wrote it is very much like our own time. I believe that, to every thing in the stock markets, there is a season. A time to buy and hold and a time when buy and hold will destroy your ability to recover. There are vocal advocates for buy and hold and there are vocal advocates for being willing to be nimble and trade – but both biases stem from the type of market in which the proponent spend his or her “formative years” and neither are appropriate for “the other” type of market. Let me illustrate:

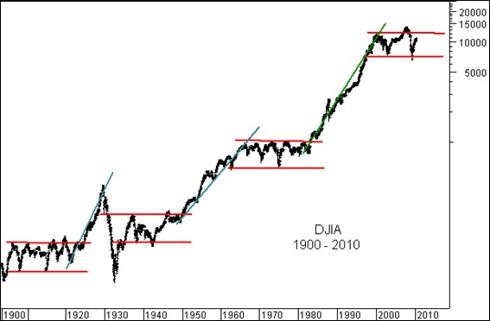

As I wrote the first time I placed this chart on Seeking Alpha (in an article here about the importance of understanding secular bull and bear markets,)

“If a picture is worth a thousand words, this chart is worth a million.”

What this 110-year chart clearly demonstrates is that secular bull and bear markets typically last a minimum of 10 years and may last as long as 20 years. So if you are an analyst being interviewed on CNBC who cut your teeth on investing in the secular bull between 1982 and 2000, you believe that the current interregnum is an aberration and that buy and hold is still the way to go. It was – back then. But, taking the long view, you can see it might really hurt you now.

That’s why The Battle for Investment Survival is worthy of your time today. Mr. Loeb wrote it at a time very similar to our own. Look at the monstrous decline from 1929 to 1933, the V-shaped rebound and then the sideways action of the next 15 years. If you agree with my conclusions from the article I first featured this chart in, you cannot help but be struck by the similar sideways action of every secular “bear market” of the past 110 years. So forget the “gurus” telling you that buy and hold will come back. Of course it will come back – in the next secular bull market. But if you listen to them now, I believe you could lose a fortune. Why not listen to someone facing the same up and down ratcheting markets that we have faced since 2000 and are likely to face for at least another year or two? If you do that, I believe the “wheat” that you will find – not without a little effort – in this tome will be quite wholesome for your portfolio.

Writing with the lessons of the early 1930s uppermost in his mind, Mr. Loeb disabuses the reader right away of the notion that there is easy money to be made. This is work. More fun than digging ditches or picking cotton or laying brick, maybe, but work, nonetheless. He also disabuses us of the cherished belief that there are safe havens or safe investments when markets decline. (He is quick, and correct, to point out that, even in the best of times, bonds lose value because our government needs a steady depreciation of the dollar in order to pay back creditors in ever-less-valuable currency. What a dollar bought in 1965 now takes nearly 7 dollars to buy.

He tells us diversification is not all it’s cracked up to be. (So did Peter Lynch, who called it “de-worse-ification.”) Loeb advocates instead fewer stocks to keep track of, but gaining depth or understanding on the ones you do hold. His point, verified by virtually every investor during last year’s plunge to 6000 on the Dow, is that when people panic they sell everything, so a diversified portfolio will fall just as much as an undiversified one. Moreover, a diversified portfolio will reduce the attention you can pay to individual stocks. And he believes, no matter how solid the company, if its stock goes down, sell it. Better to take more very small losses than one or two devastating ones. Again, the recent experience of The Crash is clearly in evidence in his strategy.

The Battle for Investment Survival is only 153 pages long. The entire rest of the book, another 153 or so pages, consists of articles by Loeb in which he comments on a variety of investing topics, as well as his opinions on the state of the country, proper ice cream sodas and all sorts of other fun, but not necessarily germane, stuff.

Beyond the investing principles I mentioned above, some other takeaways from the first 153 pages include Rule #1 – Buy only something that is quoted daily and can be bought and sold in an auction market. Liquidity is key! If you’re going to slowly accumulate 10,000 shares of a $1 stock and expect to sell for $1 in a rapidly-declining market where that is the alleged bid, I have some oceanfront property in Nebraska to sell you. That “bid” may only be for 1000 shares, or 100. The market-maker will eat you alive as you try to sell an illiquid security. You’d be like the announcer at the airport at the end of the movie Airplane!, announcing “Now arriving, Gate 22, uh, 20, um, 18, uh, 17, 16, 15…” as you watch your sale go from 1000 at $1 to 3000 at 92 cents to 2000 at 89 cents, and so on. Stick with quality names, well-followed, current in their reporting, and in an auction marketplace.

In addition to avoiding penny stocks, sucker mailings, Internet and e-mail touts, etc. build in-depth knowledge in a limited number of venues that you can stay on top of. Even further, he advises that it is better to stay in cash than to reach for yield. Even the best dividend-payers will often plunge right alongside the most rankly speculative stocks. Why? Because some people are loathe to admit their mistakes, so they sell the positions least down at that moment, but then create a waterfall of selling as everyone else does the same thing.

Mr. Loeb does not fear the word speculation. He uses it quite differently than I would but, once you understand his definitions, his strategy makes sense. To him, speculation simply means to take advantage of a capital gain opportunity with a high probability of reward – whereas investing means to seek a slow steady return that is bound to bite you if one thing goes wrong with the company, since your capital gain will likely provide a smaller cushion for error than in those items you bought that moved more.

He and I are in 100% agreement on what he covers in Chapter 9 – know your companies and know the industry! Too many investors buy a stock they hear touted and fervently hope it go up — but they have no target in mind in terms of duration to get “there”, nor any concept or where “there” is. Loeb implores you to understand “why it was opened, what one expected to make, how long it was expected to take…” Selling – and knowing why and when to sell – is more difficult, and perhaps therefore even more important, than buying.

In Chapter 12, you’ll learn, or more likely be reminded, that the goal is to buy low, not the other way around! (Although the relative momentum crowd would have you believe otherwise.) Forget relative momentum and greater fool claptrap. You should buy when /Sentiment is bearish / Prices are low relative to historical norms / Current business conditions are poor (not good!) / The particular company you are reviewing is out of favor / Dividends are non-existent or at least lower than normal. Buy when the stock is undesirable to others, and sell when the majority believes the quality has reached investment grade.

The Battle for Investment Survival is well worth reading – especially for today’s investors — but make sure you highlight the places you find the wheat. You don’t need to slog through the diversions and confusions more than once! If he was right about the times in which he was writing — and he seems to have been – and I am right that this time is similar in direction or, more accurately, lack of direction, then this may be one of the best books you could possibly read to protect what you have and be prepared for the next time buy and hold will make this game a whole lot easier.

— J L Shaefer

Where Are the Customers Yachts?

by former professional Wall Street trader and best-selling children’s book author Fred Schwed, Jr. 1940

I can forgive a lot if a book is readable. But there is absolutely nothing to forgive about Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? and it is eminently readable. More than that, like all my other selections for your consideration, this book is truly timeless. Need an example? How about this bit of wisdom about bankers, written 70 years ago. You tell me what has changed…

The conservative banker is an impressive specimen… He is at the top, or close to the top, of one of those financial empires whose destinies have been guided with such prudence, shrewdness and soundness that today the Great House has darn near as much money and prestige as it had in 1900… In times of stress, when everybody needs money, he strives to avoid lending, but usually makes an exception to the United States government. Likewise, in prosperous times, he is a mighty liberal lender—so liberal that years later unfriendly committees ask him what he thought he was thinking about, and he is unable to remember.

Or how about this, on the intellectual development and moral maturity of his fellow traders?

Wall Street, reads the sinister old gag, is a street with a river at one end and a graveyard at the other. This is striking, but incomplete. It omits the kindergarten in the middle, and that’s what this book is about.

And here is Mr. Schwed discussing technical analysis:

It is the popular feeling on Wall Street that chart readers are pretty occult professionals but that somehow most of them are broke. If you have the bad taste to ask [one] how it happens that he is broke, he tells you quite ingenuously that he made the all too human error of not believing his own charts.

The title itself comes from a delightful old story, dating from the 1870s, when some traders gathered in the harbor at Newport, Rhode Island, to admire the incredible yachts of Wall Street’s seriously rich brokers. After admiring these extravaganzas intently, one of the traders, William R. Travers, asked his companions, “Yes, but – where are the customers’ yachts?” Mr. Travers later made a sizeable fortune, without the “benefit,” we are left to imagine, of listening to brokers’ advice…

And on short-selling:

Dictatorships always immediately ban short-selling, since it is axiomatic with them that no professional pessimists are going to be tolerated.

Lest you think this too-thin little volume is a Mark Twain-like series of pithy observations and witty aphorisms, however, I hasten to point out that the advice he offers is powerful stuff, as valid in 2010 as it was in 1940.

He discusses, albeit with wit and occasional irreverence, the deadly-serious subjects of the validity of financial projections from Wall Street, big banks and their often-deleterious effect on the economy, chartists, the nature of pay on Wall Street, types of investors, churning of accounts, “investment trusts,” the forerunner of today’s mutual funds and hedge funds, each in its own circuitous way, short sellers, puts and calls (from the days some of us remember before listed options came to be), speculation, the role of cash in a portfolio, market manipulation, the difference between price and value, and, particularly a propos today and this week, the “Horizons and Limits of Regulation.”

I leave you with one more Shwedism that shows how little things have changed in the last 70 or 100 years. When he writes, “The type of customer who habitually sits in a boardroom is frequently just a gent who loves to chat in masculine [back in those days] company but who doesn’t belong to a club,” how different is that from the people who have no life beyond the message boards and chat rooms on OTC penny-stock sites who spend 8 or 10 hours a day touting a particular stock, then responding within seconds to every damn fool who dares to disagree with their vociferously and repetitively expressed opinions?

If you enjoyed the first three offerings in this Timeless Investment Classic series, I guarantee you’ll want to add Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? to your library! I leave you with the frontispiece to the original (and most reprinted) edition of this little gem as evidence that honesty does sometimes intrude upon business as usual on Wall Street:

The information contained herein, while not guaranteed by us, has been obtained from sources which have not in the past proved particularly reliable.

Thank heaven for Fred Schwed, Jr. If not for reading him some 40 years ago as a young pup in this business, and once or twice since, I might have actually believed the drivel coming out of Wall Street!

— J L Shaefer